- Home

- Martin Mundt

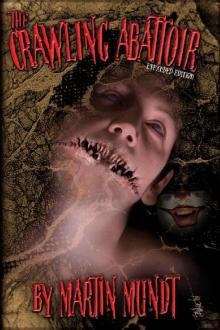

The Crawling Abattoir Page 6

The Crawling Abattoir Read online

Page 6

“If you don’t mind a question,” said George.

“Not at all. Not at all. I left all my pamphlets in my other robe, but I think I can answer any questions you may have about our faith.”

“Why are you all named Tenzin?” said George.

“And why are you all numbered?” said Marge.

“Ah,” said Tenzin the 24th, and he steepled his hands under his chin, as if thinking. “Well, in all honesty, Mr. and Mrs. Henderson, we don’t choose the numbers; the numbers choose us.”

He began nodding his head, a serious look on his face, the same look that George and Marge’s mutual fund salesman always used to such good effect.

George and Marge began nodding in time with him, just as they did with Phil, their mutual fund salesman.

“I see,” said George. “It’s just that it must get confusing, everybody having the same name, I mean. No offense.”

“None taken,” laughed Tenzin the 24th. “But really, it’s not confusing at all. All my brothers know that I’m still plain old Keanu Harrison of Scituate, Massachusetts, just new and improved, that’s all.”

“Lots of fine people in Massachusetts,” said Marge.

“Too many Democrats for my taste,” said George, pointing with his pipe. “But still good solid people, I’m told, and they know a thing or two about cold weather up there, as well.”

George was the manager of the Insulation Department in the Rehab Barn at the local mall.

“And in case I forgot to mention it,” said Tenzin the 24th. “You’ll be fully reimbursed for any item of furniture or apparel, or any knick-knack or appliance that Tenzin the First may have chosen to reincarnate himself into.”

“I thought that people only reincarnated as people, or cats, or things like that, you know, living things,” said Marge.

“A common misperception, Mrs. Henderson, but inanimate objects are people, too, as we like to say at the Temple. Four reincarnations ago, in ‘96, I think it was, Tenzin the First came back as a ball-point pen. I can tell you, we nearly had a schism trying to decide what to do when he ran out of ink.”

He chuckled.

He didn’t tell them about the times when Tenzin the First had reincarnated as a Sawyer Mark 40 Stainless Steel Surgical Bone-Saw, or a silenced Glock 9mm pistol, or the nightmarish Ice-Pick Reincarnation.

“Four reincarnations in only two years?” said George. “Isn’t that quite a lot?”

Tenzin the 24th’s smile disappeared, replaced by a pained expression, as if he had just swallowed some spoiled pork. He had spoken too freely. He had not thought ahead. He didn’t want to explain the First’s frequent turnover in souls. There was just no good way to explain electric chairs and lethal injections and exotic, designer-drug-cocktail overdoses.

“Bad luck,” is what he did say, hoping George and Marge would both misinterpret this phrase to his best advantage. “Sometimes Tenzin the First has just spectacularly bad luck. Between you and me, I think that he just doesn’t care what kind of danger he puts himself in, knowing he’s going to be reincarnated and all.”

And boy, wasn’t that the truth, thought Tenzin the 24th. He shuddered at the icicle-memory of the Ice-Pick Reincarnation again, the seemingly endless digging of graves in the Temple basement.

Tenzin the 40th entered the living room and began inspecting a copy of TV Guide on the coffee table.

“Tenzin the 40th,” said Tenzin the 24th. “That’s not him. You know the First doesn’t like to read.”

Tenzin the 40th nodded and started to inspect the TV remote.

George fidgeted.

Marge patted him on the arm.

“We’ll get you a new remote, dear,” she said.

George smiled without happiness.

“So,” he said. “Where’d you say this Temple of yours is?”

“The Temple is in our hearts, Mr. Henderson,” said Tenzin the 24th. His stomach turned inside-out as he remembered barely escaping through the sewers as the Temple in Reno burned after tear-gas canisters set the place on fire, the brothers’ spare ammunition cooking off in the flames like demonic popcorn.

“That’s nice,” said Marge. “Almost beautiful, sort of.”

“Must get cold in the winter,” said George, sensing an insulation customer.

“Oh, we have buildings, but they’re just shells,” said Tenzin the 24th. “You can get trapped inside buildings, trapped like rats with nowhere to go when the guns start to go off.”

He shook himself out of the Reno memory, stopped the memory of the gas rising, stopped sweating inside his gas-mask, stopped slamming clip after clip into his M-16.

“Material possessions, I mean,” he said, his face relaxing from a death-mask to a happy-face. “The accumulation of material wealth being a sort of spiritual prison, with the guns of greed and, I don’t know, envy going off all over the place.”

Tenzin the 40th picked up the fireplace poker behind George and Marge, testing its heft, swinging it like a club onto a skull, over and over again, a glazed smile on his face.

“That must be hard on you,” said Marge. “To just pack up and leave that way, I mean. You must have, oh, I don’t know, altars and pews and holy… things and such.”

“Oh, it’s not unusual for us to leave hastily,” said Tenzin the 24th, and his flashback began running in fast-forward, the sirens, the barricades, and that damned hostage negotiator yelling and yelling and yelling on his damned megaphone, and Tenzin the 24th yelling back, Eat shit and die, motherfucker, eat shit and die, and the M-16 bucking in his hands on full automatic, and glass and plaster and bullets flying everywhere. He wiped a trickle of sweat away from his eye. “No, no, it’s not unusual at all for us to leave hastily. The search is what’s important for us. To find the Fleeing Soul.”

“The Fleeting Soul?” said George. “What’s that? Is that some kind of Zen thing? They use that Zen stuff in basketball, don’t they? If professional athletes use it, then there’s got to be something to it, I say.”

Tenzin the 24th allowed himself an internal sigh of relief, a cleansing breath. If Mr. Henderson chose to hear Fleeting instead of Fleeing, then that was just fine. He hated explaining that title, anyway.

He heard army boots pounding down the stairs.

“He’s upstairs! He’s upstairs!” shouted Tenzin the 33rd.

Tenzin the 24th turned around and raised his hands. “Calm yourself, brother,” he said.

Tenzin the 33rd swallowed his gasping and started over.

“Tenzin the First is upstairs,” he said evenly.

Tenzin the 24th forced down the last of the flashback, the thudding of the circling police helicopters, the glare of the spotlights, the crackle of broken glass and spent bullet-casings underfoot.

“Lead the way,” he said to Tenzin the 33rd, and he walked unhurriedly up the stairs.

Marge and George followed him, and Tenzin the 40th, the 42nd and the 49th crowded in behind.

They entered a spare bedroom, where Tenzin the 28th was standing with his head bowed.

Tenzin the 24th saw the new reincarnation immediately.

“At least it’s better than the last time,” he mumbled to himself.

Stuffed animals filled the room, hundreds of them, maybe thousands, elephants and dogs and squirrels and rabbits and hobbits and Smurfs and Kermit and teddies and birds. A soft menagerie buried a bed in the corner. Tenzin the 24th flashed back again, this time to a mass grave in the woods of west Texas. He swallowed hard and shoved the memory back down below the bubbling surface of his subconscious. He knew these flashbacks were only the result of too much sacramental LSD, but a chill wiggled down his spine at the memory of west Texas, the thought of the awful, hallucinatory Ice-Pick Reincarnation, the thought of Tenzin’s Two through Twenty-Three all either dead or on Death Row. He felt like the next candy bar in a vending machine.

“Yessirree, Marge is quite the little collector,” said George, smiling. “Had a spread in Doll Universe magazine, she did, com

plete with pictures.”

Marge smiled and blushed. A framed cover of Doll Universe magazine hung on the wall.

Tenzin the 24th didn’t pay attention. He stared at the bed.

Tenzin the First stood out because the black button eyes of the stuffed animal he had possessed were alive. They followed Tenzin the 24th as he moved.

The brother-monks all assumed the position of Advanced Humility, on their knees, ankles crossed, hands behind their heads with fingers laced together, very similar in fact to the standard police pre-handcuff position.

“That’s Senor Juan of Peru,” said Marge when she realized the focus of their humility. “He’s Numero Uno in the Our South American Neighbors Collection.”

Senor Juan was a foot-tall, orange-furred, stuffed llama with a serrated, green felt mouth sewed onto his face. “Looks like you fellas got yourselves a real, honest-to-Pete Dolly Llama,” said George around a faint smirk. “No offense.”

Tenzin the 24th took no offense, because he hadn’t heard. He listened only for the Great and Serene Leader’s first words, the words that would guide this entire reincarnation.

“What should we do, Great and Serene Leader?” whispered Tenzin the 24th, even though he figured that he pretty much already knew what they were going to do.

“What was that?” said George. “I couldn’t quite hear you.”

Senor Juan smiled, and never had a stuffed, orange llama worn a look of such pure evil.

“Kill ‘em,” said Tenzin the First in a gravelly, guttural voice, as if he were waking up at three in the afternoon after a bender and he needed a shot of Jack Daniels real bad. “Kill ‘em all.”

“What?” said Marge.

“I didn’t catch that,” said George. “What’d he say?”

Tenzin the 24th cringed. It was the second time in a month that a stuffed animal had spoken to him in a voice on the edge of psychotic hysteria. He retreated into the mantra given to him when he first joined the Temple, given to him personally by the Great and Serene Leader.

“I don’t need anti-psychotic pharmaceuticals,” he mumbled. “I don’t need anti-psychotic pharmaceuticals. I really don’t need anti-psychotic pharmaceuticals.”

“You’re going to have to speak more clearly,” said Marge, tilting her head towards Tenzin the 24th, trying to catch his words.

Tenzin the 40th and 42nd and 49th stood up behind George and Marge.

“Blood,” growled Senor Juan. “Blood everywhere, blood on the walls and blood on the ceiling, rivers of blood, torrents of blood.”

“What?” said George. “Your Leader has a mighty thick accent. No offense.”

Tenzin the 24th stood up and faced George and Marge. His mantra had calmed him, had focused him.

“Did he say something about mud?” said Marge.

“I don’t know,” said George, shaking his head. “I couldn’t understand a word he said.”

Tenzin the 24th unsheathed a brightly honed machete from inside his robe. The other Tenzin’s drew their own machetes.

George and Marge understood machetes.

“Sorry,” said Tenzin the 24th. “But we’re going to have to cut you into pieces now. No offense.”

Then there were blades and slashing and squirting blood and screaming and crawling and cries of ‘Take him, take him, I’ll join, I swear I’ll join,’ and that unmistakable sickening, sliced-pumpkin-thudding sound that machetes always made.

“And for Christ’s sake, don’t leave any witnesses this time,” shouted Tenzin the First. “They’ve got the chair in this state, you know. Ouch! Fifty thousand volts’ll pucker your ass, believe me.”

“Damn,” muttered Tenzin the 24th, hacking away at a femur, he didn’t know whose anymore. “This is exactly how the last reincarnation started out.”

“And before we leave,” yelled Tenzin the First. “Somebody go find me an ice-pick.”

Emptiness, Shaped Like A Man

he name’s Andy, he always said. His full name was Anton Karel Kwiatkowski. Well, that was his name now. He was seventy-one years old, and that was true, and he said he came from Poland, and that wasn’t.

The elevator stopped at the eighth floor. The doors slid open, and a young man stepped on. Andy watched him closely.

The young man’s features were common. He had no facial hair, no visible piercings or tattoos; his expression was blank, as slack as sleep, as if he were thinking of something that had happened fifty-four years before, on another continent.

His clothes weren’t baggy or black or ragged or covered with brand-names in shaky, jagged letters like graffiti. He didn’t wear gigantic sneakers padded like lace-up beanbag chairs.

He wasn’t tall. He wasn’t skinny. He wasn’t fat. He wasn’t short. He had no acne or scars or glasses. All in all, he seemed like a nice young man, neither objectionable nor threatening, like so many young people looked to Andy these days.

He looked almost as if he had no experience of the trends and undercurrents of life that had always swept away young people. Almost as if he had stepped fully grown into this world out of a place of complete, well-lit, warm innocence. But of course that wasn’t true. In fact, there was quite a lot of deception going down on that elevator.

Andy didn’t notice that the young man’s eyes were slightly concave, as if they were designed to focus on something inside of himself.

Andy saw everything he was going to see in a few seconds, and he was not intimidated. The young man stepped to the back of the elevator, behind Andy, and turned to face front, all in a very civilized silence.

Andy ignored him.

The elevator jerked into motion, descending slowly. It was old, like the building, like Andy, like the young man.

Halfway to the seventh floor, the unremarkable young man zipped himself open. He touched his right hand to his throat, and, as if he were undoing his jacket, he opened his body from neck to crotch, his skin parting and stretching wide in the wake of his moving hand. He exposed a quiet darkness inside himself, like a chasm falling away into nothingness, like space without stars.

When he was fully open, he reached out and grabbed Andy around the neck with both hands, yanking him backwards. Andy lost his balance and fell, right through the skin-opening and into the darkness, trailing a few syllables of surprised German from his constricted throat, like guttural bubbles from a drowning man. He folded up as he fell, as if he were going backward over a railing. His feet slipped in, heels over head, and the young man zipped himself closed, just like that, with no trace of Andy or the space without stars showing anywhere.

A second later, he began to change. His face melted, his features drooping into jowls and folds and wrinkles. His hair grayed and thinned. His shoulders sagged into aged slopes. His flesh slipped down like a weighted belt around his waist. His legs bowed slightly apart.

And just like that, Anton Karel Kwiatkowski stood in the elevator again, alone, as the elevator stumbled to a halt on the ground floor.

The doors opened and an elderly couple got on as Andy got off.

“Hiya, Andy,” said the man, and the man’s wife smiled and nodded.

“Good morning to you, George, Edna. Have a fine day,” said Andy, because that’s what he always said to them.

Andy walked out the front door, caught a cab to Kennedy Airport, bought a ticket to Washington, and settled in for a long day. Once in the capital, he went directly to the Headquarters of the FBI.

“I am a Nazi,” he said to the first person he found. “My name is Max Heiliger. I was a guard at Auschwitz beginning in June, 1944, until the end of the war. I knew exactly what I was doing. You must arrest me.”

This was how a very long day began.

After fifty-four years, Max Heiliger finally told the truth; except, of course, that he wasn’t really Max Heiliger, which was the only thing he didn’t tell the truth about.

Max Heiliger himself, screaming in isolated terror, shrieking in solitary pain, fell alone through nothingness, with only h

is own dark, deluded, half-forgotten memories for company, and no one heard him but himself.

Grady heard a noise outside in the hallway.

He held a shotgun at his waist, as if it were a fire hose, as if pulling the trigger would spray death everywhere, completely out of his control. He pointed it at the door, then at the window, shoving it towards each target as if he could make the pellets fly faster by pushing the gun as he fired. He looked uncomfortable. He looked scared.

He had never fired a gun before. The shotgun was empty, because his fear of what might be out there hadn’t yet overcome his fear of loaded weapons. He had a picture of Gandhi on the wall of his den, not John Wayne. Gandhi.

But something was out there, maybe in the hall outside his door, maybe on the fire escape outside his window, and he was on its list.

He knew it. He felt it in his twitching medulla. It didn’t make sense, but it was true. None of it made any sense.

Ben Heller’s friends were being attacked somehow.

Probably attacked, Grady told himself. Three of Ben’s friends had gone into deep comas in the past few months. No diseases. No injuries. No accidents. No warning. Just zipped into instant, body-bag-cold comas.

Grady was Ben Heller’s friend.

Well, there were warnings, at least Grady thought so. The problem was, only he recognized them as warnings.

First, the three people in comas were friends who had somehow crossed Ben. They were three names on a shit list. There was Joe McManus, who had once beaten out Ben for some grant money. Apparently Ben’s research proposals, “The Practical Applications of the Kabala,” “The Physics of Mysticism,” and “Machine Intelligence Adapted to the Construction of a Golem,” didn’t draw much interest. Ben had resented Joe ever since. Cheated him, Ben said.

Then there was Annie Carter, and well, that situation was common knowledge and very old news, but Ben had never gotten over it. She lied to me, Ben said.

Last there was Sam Verona, and that was simple. Ben never really forgave anyone who uttered the word kike, did he? Even if it was ten years in the past, said in anger, regretted and apologized for. He’s an anti-Semitic bastard, Ben said.

The Crawling Abattoir

The Crawling Abattoir