- Home

- Martin Mundt

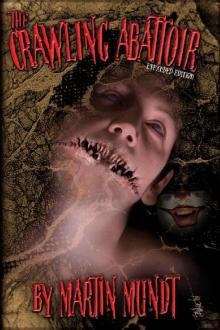

The Crawling Abattoir Page 4

The Crawling Abattoir Read online

Page 4

“I haven’t got one of these, though,” he said, and he threw it clattering onto a pile in his cave. Then he crawled onto his cash for a decade or two of rest, because, after all, he was a dragon.

Bug Mess

hat’s that smell?” said Kara, sniffing at the air in the kitchen of the house they were rehabbing.

Wayne stepped into the kitchen and stood next to her. He inhaled.

“Bug mess,” he said in an instant. “Probably cockroaches, maybe crickets. And a bad infestation too, if I’m not mistaken.”

“Oh, great,” said Kara, propping her hands on her hips. “That wasn’t here before, before we bought the place, was it?”

Wayne shrugged.

“Mating season,” he said. “Stirs ‘em up.”

“Great,” said Kara again. “Now we have to call an exterminator.”

Wayne turned and stared at her.

“No way,” he said. “We can take care of this ourselves. I worked my way through college as an exterminator, you know.”

“Yes, I know,” said Kara, rolling her eyes. “You’ve only told me the stories about a million times.” She shivered. “I never could figure out why anyone would be so proud of killing bugs.”

“It’s a proud profession,” sniffed Wayne. “You know I love you, honey, but I’ll never understand why you don’t appreciate the exterminating game. I mean, being a best-selling novelist is great, but being an exterminator, now there’s a real adrenaline rush.”

She hugged herself and rolled her eyes again.

He put his arm around her waist and pulled her tight against him.

“And you’re the ultimate beneficiary of all those churning endorphins and testosterone, you know.” He switched into his deepest Barry White voice. “You know Bug Man loves you, don’t you, baby?”

“Oh, god, not Bug Man,” she sighed.

They heard a scurrying sound, like millions of little feet, through the walls.

Kara lifted her skirt a few inches and looked down to make sure that her feet were the only feet standing in her shoes.

“Please,” she said. “Let’s just call a real exterminator.”

“Bug Man is insulted,” said Wayne, and he walked out the door into the garage, where his leftover extermination equipment was in boxes.

Kara stood in the doorway and watched him yank boxes open, the ripping tape echoing in the empty garage.

“Aha!” cried Wayne. “Here it is.”

He pulled out a baseball cap, sectioned into orange and yellow pie-wedges, with springy, plastic-eyeball-tipped antennae wiggling on top.

“Oh, god, please not Bug Man,” Kara moaned, hugging herself harder. “Bug Man is just so totally… strange. I wish I’d never mentioned the damn bugs.”

“But you did,” said Wayne, hanging a pair of orange plastic goggles around his neck.

“I really wish I hadn’t,” whispered Kara.

Wayne buckled a tool-belt around his waist. He pulled on an orange-and-yellow vest, with a silhouette of a cockroach lying on its back, pinned to the ground, the fretboard of a guitar piercing its thorax.

‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Exterminators’ was printed in a circle around the mounted bug.

Kara worked her fingers into her hair, pressing her palms against her temples.

“How long are you going to keep that stuff?” she said. “That insecticide is probably dangerous, it’s so old.”

“Not for a trained professional,” said Wayne, and the plastic eyeballs swayed and wavered around his forehead. “Besides, you knew all about Bug Man before we got engaged, and you still married me, till death do us part, didn’t you?”

“Right now, I really wish I hadn’t.”

He found a second box filled with a spray cylinder and cans of insecticide. He began rotating the cans to read the labels.

“Elvis strength,” he muttered. “No, that’s only good for squishing a few bugs in corners with blue suede shoes.”

He read the next label.

“Beatle strength.” He considered. “No, that’s really just for beetles. Grateful Dead strength, no, too mellow, and besides, it smells like pot. Bob Killin’ strength, no; this is the earlier, folkier version. It just doesn’t have the amps for this job.”

He slid the last can out of the box.

“Sid Vicious strength,” he read and grinned. “Yeah, that’s what we need. You can kill dogs with this shit if you’re not careful, but I’m…”

“A trained professional,” Kara finished for him.

He smiled up at her, pouring the last few grains of Sid Vicious powder into the sprayer.

“It’s showtime,” he said, grinning, and he swung the aluminum cylinder onto his back, settling the straps on his shoulders.

“I knew this house was too cheap. I wish we hadn’t bought it,” said Kara, a touch of Johnny Rotten sneer in her voice. “I hate bugs.”

She hated the fact that she hated bugs, but she still hated bugs.

“Never fear,” said Wayne. “Bug Man is here.”

He stretched the goggles over his eyes.

“Oh, god,” said Kara as she stepped backwards into the kitchen. “I just don’t get it. You’re so normal most of the time.”

He handed her a second pair of goggles as he passed her going into the kitchen.

“Come, join me in the hunt,” he said.

He dropped to one knee in front of the sink and opened the cabinet. The stench jumped out, pawing and licking both of them like a big, gangly, sloppy dog which had just been doused by a skunk. Kara covered her mouth and nose with one hand while fumbling to fit the goggles over her eyes.

“Oh, god, what is that?” she mumbled behind her fingers.

“Bug mess,” said Wayne, and his nose twitched.

The inside of the cabinet looked like disassembled cat intestines, an inch-thick layer of insect-droppings on the floor, stalactites of shiny feces hanging from the pipes. The colors were all the hues of the hemorrhagic-fever color-wheel, half-digested green, deathly pale white, open-wound pink, bleeding orifice red.

“Shit,” said Kara.

“Feces,” corrected Wayne.

“Oh, god, Wayne, there are bones in there,” Kara pointed at thin, curving shapes under the colored goop.

“Garbage,” said Wayne. “Chicken bones. It attracts them.”

“I didn’t know fried chickens had tails,” Kara said, pointing at a series of small bones that curled like a cat’s tail.

Wayne scooped up a short strip of the bleeding-orifice-red paste and held it under his nose. Then he reached out the tip of his tongue and tasted it.

“Ewwwwwwwwwwwww,” wailed Kara, and she made a face that looked like, well, you know what it looked like.

“Fresh,” he said. “And definitely cockroaches. But I don’t know what kind. I must be getting rusty. I used to know them all.”

He rubbed his finger clean on his jeans.

“God, and I actually let you kiss me?” said Kara, and she curled her lips into a shape like a twisty straw.

He pumped pressure into the cylinder on his back, then waved the nozzle around the inside of the cabinet, poking into corners, coating the joints.

The plastic eyeballs bobbled under the sink, plonking against wood and aluminum as he twisted and turned to spray Sid Vicious powder into every nook and niche, getting him better coverage than he ever got on the radio.

They backed out from under the sink.

They heard a solid, sliding, slipping, skittering sound inside the walls and the ceiling and under the floor, like thousands of Chihuahuas with untrimmed toenails trying to make hairpin corners on newly waxed linoleum.

Wayne followed the sound into the dining room, then the living room, then the front hall by the staircase.

“Aha, got ‘em on the run,” he said. “They can’t stand Old Sid spitting on ‘em.”

“Let’s go sleep in a hotel tonight,” said Kara, her eyes big behind the goggles. “I hate bugs.”

&nb

sp; The noise got louder in the hallway, as if every pipe, every conduit, every space in the walls were filled with scrambling, scrabbling cockroaches.

“No can do, honey,” said Wayne. “We’re homeowners now. We bought the house, problems and all.”

“I wish we hadn’t,” said Kara. “I really wish we hadn’t.”

She felt tiny shivers through the hardwood floorboards from waves of tiny, spindly feet, as if the house’s skin were crawling.

The sound flowed down from the ceiling, down through the walls like a million-legged waterfall.

“They sound like they’re everywhere,” said Kara, balancing on one foot, the better to have less physical contact with, well, with everything.

They slowly lowered their faces, as if they could watch the sound descend. Wayne pointed at the latched panel behind the stairs.

“The crawlspace,” he said. “Of course. That’s where their main colony must be.”

They knelt in front of the panel. Wayne pumped up his cylinder. He pulled a flashlight out of a loop on his belt. He opened the panel, and they poked their heads inside. He crisscrossed the darkness with the flashlight beam.

Tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of eyes reflected the beam, and worse, millions of tiny, sharp teeth glittered like the inside of a huge geode.

Piles of cleaned, smoothed bones, leg-bones and ribs and skulls from squirrels and snakes and rabbits, and one large skull that looked suspiciously like an Irish Setter named Luke that Kara had seen on “MISSING!” posters plastered all over the neighborhood filled the crawlspace.

“Well, we found ‘em,” said Wayne.

“Is that an empty shoe back there?” said Kara.

Wayne swallowed hard.

“I didn’t know cockroaches had teeth,” said Kara. “Wayne, do cockroaches have teeth?”

“I guess we’ve discovered a new kind,” he said.

“I really wish we hadn’t,” said Kara.

Then the screaming started.

The Worst Clown In The World

o where is this bleeping kid’s bleeping birthday party?” Slappo the Clown yelled into the pay phone at Dubnick’s Deli. “I can’t find 3012 Waterloo anywhere, Jack. Where the hell is it?”

Slappo stood at the front of the deli, his back to the counter and tables. His white pancake makeup cracked in his wrinkles, so that his face looked corrugated. He was over fifty, maybe over a hundred and fifty. His lips were blue, but jagged and lopsided, as if his hand had been shaking while he did his makeup. His nose was covered in blue makeup. He had drawn an exclamation point over each eye, but they only served to make his scowl look dangerous, as if he were Psycho the Clown. He wore a rainbow fright-wig.

“Goddam it, Jack, I know I’m late,” Slappo yelled into the phone.

Slappo looked bad. Tired. Bitter. Angry.

The customers looked at Slappo, but not as they would look at a skilled, beloved clown. Rather, they watched with horror, as at a car wreck, a teeny, tiny Volkswagen that had spilled the bloodied, broken bodies of a dozen clowns on the street. Mothers turned their children’s heads away from the foul-mouthed Slappo. Fathers twitched, driven to do something about Slappo’s demeanor and language, but hesitant to approach him for fear of the hair-trigger psychotic menace he radiated. This was Chicago. People still remembered that John Wayne Gacy too had been a clown.

“Goddam it, Jack, I know this is my last chance. You’ve told me that a dozen times,” Slappo screamed, spitting into the phone. “Just get me some bleeping directions and let me take care of the bleeping merriment, OK?” His hands shook; a vein in his temple throbbed. “Get me some bleeping help here, Jack. You’re my agent, right? Well, do whatever the hell it is that agents do besides bitching at me and taking fifteen percent and get me some directions. Just a little help, that’s all I want, and then I’ll take care of the bleeping kids, just like I always do.”

The customers could have interpreted that last sentence in one of two ways. First, that Slappo would get a grip on himself, transforming into a clown of merit and joy, enchanting and delighting a party full of wide-eyed six-year-olds. Or, second, that he would pull out an AK-47 and hose down a room full of wide-eyed, terrified six-year-olds, transforming the party into a horrific, bloody tangle of prematurely obliterated young lives. There was little doubt which interpretation the customers entertained.

“All right, all right, I’m calm, I’m calm already, goddamnit,” said Slappo, closing his eyes like blue dots under the exclamation points. “But you better call me back when you have directions, Jack. Don’t leave me hanging here. Remember, I know where you bleeping live. The number’s 555-2525.”

Slappo hung up, the clack of receiver hitting cradle echoing throughout the deathly silent deli. Slappo took out a cigarette and stuck it between his lips.

“Christ, I hate my life,” he whispered around the filter as he fumbled for a match. “If I could just be funny today, really funny, just for this party, then I could get myself back on my feet. Where the bleep are my bleeping matches?”

“Here,” said a man who walked up to Slappo. He was tall and skinny. He wore a black, wide-brimmed hat that dipped low in front to obscure one of his eyes. He wore a black-satin, floor-length cape and a red scarf wound around his neck, one end tossed back over his right shoulder. “You can borrow this.” The man produced a red, rubber clown’s nose by sleight-of-hand. He held it in front of Slappo’s face. “This nose once belonged,” said the man, “to Count Blotto Von Bingen-Bongen, the most famous clown in all of Imperial Germany, the greatest clown ever to perform in front of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the only clown ever to make Bismarck snort beer out of his nose with laughter. Count Blotto Von Bingen-Bongen, the inventor of the spinning Iron Cross, the eye-smudging monocle and the dueling-sword joybuzzer, all great icebreakers at parties. Count Blotto Von Bingen-Bongen, the funniest Teuton ever, the man who made Prussia synonymous with comedy. I’m certain his nose will bring you good luck.”

The man pushed the squishy red nose onto Slappo’s own blue nose.

“Hey,” said Slappo in a nasal voice, as if he had a cold. “Thith smellth funny.” He sniffed. “Really funny. Did thomebody die in here?”

“Of course it smells funny,” said the man, smiling, laughing. “It smells funny. It looks funny. It feels funny.” He reached out and squeezed the nose, which beeped. “It even sounds funny. You can’t not be funny in this nose, Slappo.”

Fathers relaxed throughout the deli. Mothers turned their babies’ faces toward Slappo. The babies gurgled and grinned and guffawed, clapping tiny, chubby hands together in wonderment and delight, grinning, though that could have been gas.

Ernie, the guy who ran the meat-slicer, chuckled, and Ernie had not chuckled since 1984. Vondeen, the waitress, had never seen Ernie in anything but a foul mood, and she liked what she saw.

“There’s something going to develop there,” whispered the caped man to Slappo behind an upraised, conspiratorial hand. “And it’s all because of you, Slappo. Everybody loves a clown, you know. By the way, 3012 Waterloo is just north of here. A five-minute walk.”

“Thanks,” said Slappo, and then he slitted his eyes. “Hey, who are you, anywayth?”

“You can call me Mister E.S. Trainjer, Slappo,” said the man.

The giggles from the children could no longer be contained. Babies laughed, pointing at Slappo. Toddlers, being more sophisticated, tried to hide their smiles behind their hands, looking at parents to see if laughing were the grownup thing to do.

“Whath thith gonna cothsth me?” said Slappo, eyes still wary, waiting for the shakedown.

“Nothing, Slappo,” said Mister E.S. Trainjer. “Just make people laugh.”

“Jutht remember, I didn’t sign nothing, and I don’t owe you nothing,” said Slappo, and he pointed at Mister E.S. Trainjer’s chest with his finger. He remembered the unlit cigarette still between his fingers. “Hey, you got a mathsh up that thleeve?” he said. “I’d kill for a thigarette.

Can’t thmoke around the rugrath, y’know. God forbid you thould thunt their growth, the little bathdards.”

All the parents in the deli guffawed, tears streaming down their cheeks. Wasn’t Slappo just so right about children, the little bastards, and hadn’t they each thought the exact same thought about cigarettes stunting their children’s growth a thousand times? Only it had never been as funny as when Slappo said it.

“Sorry, don’t smoke,” said Mister E.S. Trainjer. “You better get going, Slappo. You’re late. Oh, and, Slappo, break a leg, OK?”

“Yeah, yeah,” said Slappo over his shoulder as he pushed open the door. “Jutht remember, I don’t owe you nothing.”

“Just make people laugh, Slappo,” said Mister E.S. Trainjer. “Just make people laugh.”

Slappo stalked off down the sidewalk, hauling his red-polka-dot covered magic suitcase, his bulbous clown-shoes smacking the concrete. He continued to scowl. He really needed that cigarette.

He was a sad and angry and cruel and bitter and sarcastic and small man, often all six at the same time. He had been a clown his entire life, but he had never been a funny clown, unless by funny you meant odd; an eccentric; a vaguely dangerous, mumbles-to-himself-on-the-street loner; an undiagnosed, borderline-delusional, bipolar personality barely one small step removed from raving homelessness, imminent arrest and heavily drugged, involuntarily padded confinement. He wasn’t a funny clown, unless you considered a nun having a stroke to be funny. It’s hard to screw up being a clown, since kids just naturally like clowns, and adults can always look at a clown and say to themselves, hey, my life may suck, but at least I’m not that sorry son of a bitch, handing out discount coupons in front of a cell-phone store or making colorful balloon animals that were more like squeaky balloon-animal entrails. But Slappo had screwed it up, over and over again.

He had started out as Buzzo the Clown, back in ‘79, but he’d gone nowhere. Then there had been that awful incident in ‘81, when he’d slapped around a birthday-boy pretty bad in the middle of a party, put the kid in the hospital, broken jaw, broken arm, knocked loose some baby teeth into the birthday cake. Slapped him around pretty bad before the butler and the au pair managed to pull the swearing, spitting, bitch-slapping, polka-dotted fiend off the squealing little brat.

The Crawling Abattoir

The Crawling Abattoir