- Home

- Martin Mundt

The Crawling Abattoir Page 2

The Crawling Abattoir Read online

Page 2

The shivering, black-lace orgasm is my signal, and I dutifully hug her legs, lift her up, cut her down. The approach of the scythe is marvelously erotic, but she refuses to consummate the act, prematurely orgasming every time. She will not remove the last veil to fulfill my fantasies. I pray that she is not hopelessly perverse, delighting only in teasing me. She is almost willing to kill herself for me, and that is worth something, isn’t it?

Be strong, Dead. I can write no more letters. We are through.

Yours nevermore,

Rex

December 20

Dear Dead,

Your ad still appears! I cannot describe my relief. I thought that I must surely have lost you forever by now.

I have severed my relationship with Vicki. My hopes have been strangled. She is nothing but a dilettante of death. She is happy to be alive. She revels in being alive. She seeks to remain alive forever, at least to endure forever undead. For all her sonnets to death, for all her paintings of graves, for all her self-portraits in coffins, she is nothing but a poseur in the valley of the shadow, a weekend corpse at best.

She taunts me for my desires, and shrieks at the top of her lungs that there is roadkill enough in the world for the likes of me. She knows precisely how to wound me. She has the ability to make necrophilia seem somehow dirty.

I fear we only stayed together for the asphyxiation.

I left her to her fake fangs and her goblets of cow’s blood and her collection of coffin coffee mugs. Good riddance.

I am free, but I am depressed. I am not afraid to say it.

I have begun working as a suicide hotline volunteer again, cruising for potential mates, a thing I had promised myself I would absolutely never stoop to again. I am pitiful.

I don’t deserve such ethereal flesh as yourself, but I hope to still have some small chance to win your heart.

Thinking of you in your time of need,

Rex

January 9

Dear Dead,

I do not know what to do.

Vicki calls incessantly, filling my answering machine alternately with threats of hellish revenge for my spurning her and with pleas of reconciliation worthy of Renfield.

She follows me, although only after sunset. She leaves gardening spades tied in bundles at my door like roses. She spray-paints crosses on my car.

She says she loves me, but she will not kill herself.

She would be such a wonderful girl, if she were only dead.

And still you do not reply. I cannot tear the image of your bullet-hole out of my head. I am torn between the two of you.

What can I do?

R.I.P.

Rex

January 20

You Damn Dead Bitch,

Did you think I wouldn’t find out where all of Rex’s bodies were buried? He belongs to me, meat and blood and bone. He’s bound to me with vampire spells, so lay off.

If I ever get my hands on you, I’ll kill you, or whatever.

All Hail Lucifer,

Victoria Unangelica Vampirus

PS My Lord and Master Satan (All Hail Lucifer) has told me telepathically that my revenge will be sweet. Flames will rise all around you in a lake of burning oil, and Satan (All Hail Lucifer) Himself will hold your head under the sheets of fire with His iron grip.

Rex will be mine forever.

January 25

Dear Dead,

Vicki and I have reconciled. I think I can speak for her as well as myself when I say that we are deliriously happy.

Yesterday she called and asked to see me one last time. She said that she had a surprise for me.

I went to see her. You had not written, and I had nearly given up hope of our love. There was no reason for me not to see her, was there? Was I wrong?

Her door was open. It creaked as I entered, as it always creaks when I enter. Black and red candles burned everywhere. I heard a stool topple, and I saw the surprise which she had prepared, swaying for me in the wavering candlelight.

She squirmed at the end of a white silk noose, her shadow skittering across the walls in the light on the candles. One more asphyxiation for me, for us.

Her army boots were old.

Her dress was new.

Her time was borrowed.

Her lips were blue.

She convulsed inches above the floor in a wedding dress, the lace train snaking across the carpet as she kicked her legs. My heart broke. I loved her so much at that moment that I forgot to cut her down.

Perhaps she changed her mind in mid-air, and tried to squirm out of her noose when I made no move to help her, but of course that lasted only for a moment. Perhaps this was just her special way of proposing, and she really had no intention of consummating the hanging. I’ll never know for sure. All I do know is that she had drawn a chalk outline of herself on her bed, waiting for me.

In any event, she had her usual orgasm then – or may I congratulate myself for allowing her to hang longer than usual and say that she had several? – I just let her die.

I love her now more than ever, more than I thought possible.

Goodbye, Dead. This time it is truly over between us.

In loving memory,

Rex

Nightfighter

dozen German bombers, Dornier 17’s, flying pencils they were called, raided West Malling airfield. They dropped their bombs on hangars and repair sheds and barracks, and then they sped off southeast, skimming tree-tops, gone before anyone hardly even realized they were there.

They were supposed to have raided an airfield called Biggin Hill, but, all English fields and aircraft parks looking similar, especially at high speed, low altitude and twilight, they made a mistake. This was called being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The sun had just set as the nightfighter took off after them.

A red dragon, red as the Union Jack, red as Empire, three times the length of one of the bombers, climbed from a wood, his huge bat-wings sweeping the air every few heartbeats. He slid behind the last flying pencil, unseen, unreal, entirely fictitious, and studied the plane’s tail, keeping pace with easy, sinuous flaps of his wings.

He closed his jaws on the tail, twisting and wrenching it off. The bomber faded, like its hamstrings had been cut, then fluttered and tumbled to the ground. The dragon snapped twice more before the plane dropped out of reach, tearing out two huge mouthfuls of cockpit before the plane slammed into a field and started to burn, with only half a pilot and half a gunner inside.

The dragon chased the remaining bombers, who had not seen the attack. The dragon saw them, however, by the little flames of their exhausts.

“Bloody Germans,” he muttered as he flew, and he meant this both figuratively, in reference to their temperaments, and literally, in reference to his own preferred cuisine.

He came abreast of the rearmost bomber and poised himself to snatch another Nazi out of the English sky. Then a long, serpentine shape charged him from above, a shape blacker than the floor beneath the Turkish carpet in the furthest back corner of his cave.

He rolled to his left, and the black blur of the second dragon snapped his fangs on air as he rushed past, the snap itself being sufficient to terrorize most opponents. The red dragon felt a sting, even as much as a slash, along his ribs. He bled deep red blood into the dark air.

He twisted and saw the black dragon uncoiling from his turn some fifty yards away, straightening for another charge. No dragon had attacked him in centuries. Dragons did not fight dragons. It simply was not done. Humans were proper prey, and cattle, horses, unicorns, griffins, even hens or leprechauns in a pinch, but not a brother worm.

He hovered.

The black dragon charged, golden claws spread, red eyes wide, with little black crosses for irises, like a Teutonic coat of arms come to life. He had a German astride his back, booted legs adangle over scaly shoulders, leather helmet and goggles strapped on his head so tight there were indentations in his skin, the ribbons of his National Soc

ialist hero-medals flapping on his flight-suit, a sword gripped in both hands like a cricket bat. The sword dripped with the red dragon’s own sacred blood, blood rarer than a hippogriff’s, more ethereal than saint’s breath, his life and soul, fluid and flowing and hot.

“Bloody Germans,” he muttered. He spat out a sliver of Perspex from between his teeth.

The black dragon charged clumsily, a consequence of the Luftwaffe man being deadweight and off-balancing, thus inhibiting a dragon’s instinctual corkscrewing, coiling, helical, spinning, rolling grace.

The black dragon charged and missed, missed with vicious, Jurassic jaws, missed with golden front claws and golden back claws and even missed with the supersonic whipcrack of his razory golden tail-spike.

There was no dragon-grace in the charge, no preening and no plumage, no majestic shrieking to make the approaching food feel privileged just to be food for such a magnificent, crowned and throned beast. Just a goat’s rush of a charge, with a Nazi lashed to his shoulders with leather straps, swaying wildly from the waist up like a Prussian bowling pin that had been sideswiped and spun, struggling to decide between staying upright and falling down.

The red dragon inverted to evade the rush, trying to liberate the German’s head from his shoulders with an upside down and backwards bite. This contortion was no great feat for a dragon, except that the flat of the German’s blade, spinning like a propeller, smacked his teeth, a firecracker of sparks popping inside his mouth. He bit his own tongue, his own splendid, forked, and fiery-red tongue, and it was much worse than when a human bites his tongue, because dragons are so much more stupendous than humans.

He dropped down to the ground, cracking off branches and landing with a thump in a green mist of stripped, crackling leaves.

The black dragon raced to catch up the bombers, because his job was to protect the planes, and not engage in epic but pointless battles with other dragons; besides, the German used spurs made of honed Krupp steel, the length of his forearms.

“Bloody Germans,” said the red dragon, except he said it more like Blawey Urmunz, because of his swollen tongue, and then he flew back to his cave, stopping only to retrieve the bomber’s tail as a trophy.

Flying Officer Howard Trevor stopped peddling and examined the forest trail on which he was riding. Forward or backward, the views were identical, like two ends of a circle fitted together seamlessly, like the Ouroboros worm swallowing its own tail.

He had started riding his bicycle at midnight, and it was now almost four in the morning. He was only supposed to have ridden about five miles, but he felt as if he had ridden more than twenty down country lanes and trails and paths, and even fields, when the trails and paths disappeared beneath grass.

He knew he had somehow gotten himself completely turned around, cycling up this dark hill and down into that black glade, all the while beneath shadowy trees, and during pitch-dark, can’t-see-your-hand-in-front-of-your-face, blacked-out, moonless night, and with his head pounding under the bandage where he had whacked it on the instrument panel of his Spitfire during his last landing; well, his last controlled crash, more like. His poor old Spit had died a hero, wrecked beyond repair.

He winced at the memory. It had been his second heroic wreck, his second time ambushed, his second thumped head, and with not even one German shot down to put in the balance against his frustration. He was sure his Captain was glad to see the back of him when he was “volunteered” for this new assignment. He was just plain bad luck, a black cat, a broken mirror, a ladder to be walked under.

Now he was lost to boot.

And he was going to be late.

“I didn’t think there were this many miles of road in Kent,” he said to the trees. “I didn’t think there were this many miles of road in all of England.”

He pushed off again, stones crackling under his tires, moving forward, as best he could tell.

He reached a hill, and his pace slackened to less than a walk. He stood on the pedals, forcing one down, then the other, like he was climbing the Great Pyramid all the way to the top.

He thought he knew the area well, from the ground and the air, but he didn’t remember ever seeing this little hill before. The oaks looked dry and brittle, but still massive enough to build Nelson’s navy.

When he came to a small meadow on top, he couldn’t see any lights; he couldn’t see any roads; he couldn’t see any smoke from locomotives or factories or villages.

He felt very alone.

He stopped under open sky, the dimmer stars already being washed out by the beginnings of sunrise. He leaned himself and his bicycle on his left foot, knee-deep in grass and wildflowers.

He saw a cave-mouth, a black arch in a bald knob of rock, the hill’s absolute peak. Pieces of German airplanes littered the meadow, a Dornier tail and a Messerschmitt wing and a mangled Focke-Wulf cockpit, but nothing whole.

He dismounted and rested his bicycle against the rock. He inspected the nearest piece of wreckage, the starboard gull-wing of a Stuka dive-bomber. The wing had been torn off about a foot from its root, its edge ragged as an ax cut. It wasn’t burned. There were no bullet or shrapnel holes.

He examined a few other partial carcasses and found the same: all hacked off their parent planes as if by a huge ax, but no fire or bullets or shrapnel. He had no doubt that the Prime Minister could tear apart a Nazi plane in this manner with bare hands, but he was at a loss to understand what else could.

There were pieces from two dozen planes in the meadow, as if the Luftwaffe had dropped their own aeronautical version of Stonehenge onto the spot.

He shrugged, filing away the mystery for later.

The cave was undoubtedly his destination. It fit exactly the particulars which he had been made to memorize by the RAF Colonel who had given him his orders five hours earlier. He had no written orders, since his mission was secret beyond the use of paperwork. Trevor had never heard of anything beyond the use of paperwork in the RAF. Even worship and death, the military way, had paperwork, and he was quite certain he would have to send back the proper forms from the afterlife when he got there.

But this mission generated no records, nothing to be spied out or leaked or decrypted or monitored or confirmed or ever proved to exist in any way. Just the nameless RAF Colonel, the memorized verbal orders, the bicycle and an immediate midnight trip into the dark countryside. Even the bicycle’s registration number had been filed off. He had filed these mysteries away for later as well.

He entered the cave, just ahead of sunrise, pleased to be right on time after all.

“Group Captain Drake, sir?” he ventured into the gloom. “Flying Officer Trevor reporting for duty. Is anyone there? Group Captain Drake?”

The cave was, well, cavernous, lit by lanterns suspended from the ceiling by chains. It was like a museum, or rather like a museum which had been picked up, rattled and shaken around by an angry giant until everything inside was smashed and broken and mixed together and then poured into a cave in a hill in the Kentish countryside. Exactly like that.

There were swords and spears and knives and bows and mismatched pieces of armor, from dented Roman breastplates to Elizabethan cuirasses perforated by dozens of holes. There were helmets, hats with plumes and leather flying helmets, top hats, spiked helmets that had bowed to the Kaiser, skullcaps and kepis and turbans and feathered headdresses and peaked Luftwaffe hats. There were arrows by the hundreds, and flintlocks and muskets and Maxim guns and Mausers and crossbows and the bronze barrel of a culverin even, straight from the deck of the Duke of Medina Sidonia’s flagship.

There were torn sections of Zeppelins, broken struts and engine cowlings from Fokker triplanes, parachutes, the gondola of a Montgolfier balloon, saddles, flags, pennants, pennons, standards and signal flags, some still on flagpoles.

There were vaults of amethysts and sapphires and pearls, gold bars and silver plate and coins minted by a hundred different heads of state, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus lying nose-

to-nose in the dust with Philip II of Spain. There was cash, a great hill of bundled banknotes, thick as twenty mattresses, with a deep and undulating indentation, as if from a gigantic resting body.

There were bits of sails, umbrellas, and not a few pitchforks and pikes and lances, some with the bones of fists still gripped around their handles.

There were a lot of bones, human and animal, and some that looked like neither, willowy and green like the bones of elves or leprechauns. Trevor stared at a boot, a boot holding a clean, white leg-bone and an Enfield .38 No.2 Mk.1 service revolver still in its holster. There were hundreds, maybe thousands, of spent bullets on the floor, kneading his feet through the soles of his own boots.

There was even more, a trash-bin of history, centuries of stuff, crushed, bent, perforated, dented, rent and torn to pieces, all tossed onto sorted piles like the cones of volcanoes, the money, the hats and helmets and armor, the weapons and bones, and everything notched with teeth-marks, but too big for teeth-marks.

Teeth-marks would explain the junk though, because then everything would be bite-sized, if one allowed for an extremely generous bite, say, a dragon’s bite.

He chuckled at his own civilian surplus of imagination, too much bookish fantasy and radio-serial fancy.

He heard a huge, scaly, slithering, winged noise behind him at the cave-mouth, like a radio-serial reptile might sound.

He turned around.

A red dragon squeezed through the door. He had a face like a mace with eyes, eyes black and as large as Trevor’s head. He had curved, oversized fangs sticking above and below his jaws like a nightmare zipper. He had a flame-red mane of feathers running down the back of his long neck. His claws clacked on the stone floor.

He pulled himself all the way into the cave. He shook like a dog, from head to tail, machine-gun slugs flying out from under his scales and clattering across the walls like a strafing run.

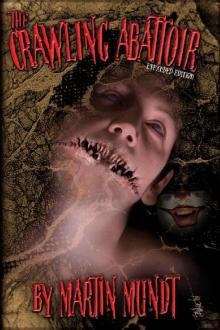

The Crawling Abattoir

The Crawling Abattoir